New research suggests that the tree species in the eastern U.S. that are most vulnerable to the impacts of rising global temperatures will require human intervention in order to adapt to changing climatic conditions. Photo by Patrick Jantz.

The implications for this disruption are not entirely clear. As tree species migrate or die off, what will the impact be on the animal, bird, fish, plant, and even microbial life that exists in all 59 national parks? These threats to complex ecosystems are similar across the country, but tend to be understudied, as conservationist E.O. Wilson argues repeatedly in his recent book Half-Earth, Our Planet’s Fight for Life.

The new study acknowledges that climate change “is disrupting species interactions and altering ecosystem carbon and nutrient dynamics” while remaining tightly focused on the biggest part of the ecosystems in question — trees.

“This study integrates state-of-the-art methods and concepts that have been developed in the last 10-20 years to provide practical tools for forest land managers regarding the vulnerability of Eastern forests to rapid, anthropogenic climate change in the coming decades,” said Janet Franklin, a sustainability scientist at Arizona State University who reviewed the study.

“It starts with simple and frequently used models that assume that tree species will have to track their climatic comfort zone (move north or uphill as things warm). But then by also incorporating simple assessments of seed dispersal, the study shows that even if suitable conditions for a species are predicted to expand, rather than shrink, in the region, human land use has fragmented continuous habitats, and climate change may also increase tree diseases and insect pests. These combined factors make some species and some locations more vulnerable than others.”

The Woods Hole researchers developed models and drew conclusions by studying forests in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in eastern Tennessee, the Shenandoah National Park in central Virginia, and the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area between eastern Pennsylvania and northwestern New Jersey. Their work was conducted to help national park managers develop effective strategies for climate change mitigation.

Rogers said it’s common to see a range of the Smokies, for example, blotted with patches of dead trees caused by disease or pests that are now able to survive the milder winters the region has been experiencing. Species impacted the most by such threats include balsam fir, red spruce, eastern hemlock, white ash, northern red oak, white oak, and American beech, the study found.

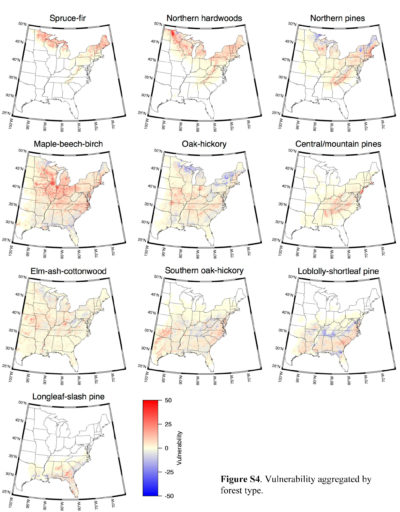

The Woods Hole research produced high-resolution maps ranking tree species’ vulnerability. The maps are seen as tools to more precisely direct park managers in prioritizing how and where to battle climate change.

“Although planting forests is not a typical practice in National Parks whose mission is conservation and preservation, this assessment could make their management actions more focused and effective,” Franklin said.

“For example, if a high elevation species is vulnerable to climate change and also insect pests, expensive treatment of the insect outbreaks could be focused on locations where the species is more resilient to climate change.”

In the Smokies, the researchers suggest that the eastern hemlock could benefit from such strategic interventions.

Rogers added: “Park managers understand they must manage the ecological integrity of their forests and make tough decisions about how to spend limited resources in a constantly evolving environment.”

The study did find a few bright spots. While northern and high-elevation tree species tended to be most vulnerable, species appear to be more resilient in West Virginia, where the terrain is more complex and intact for greater stretches.

The Woods Hole research is part of a larger NASA-funded project also looking at the northern Rocky Mountain states. There, climate change is contributing to drought, more forest fires, and mass tree die-offs due to blights and pests once controlled by far-colder winters.

John Gross, an ecologist with the National Parks Service’s Climate Change Response Program, said last June in an interview with the radio program Living on Earth that climate change is linked to coastal erosion at seaside parks, the melting of permafrost in Alaska, and the receding of glaciers in Glacier National Park.

Species migration — or at least the potential for trees, plants, and animals to move and adapt to warming temperatures — is a constant and widespread concern. Park boundaries are rendered meaningless under such conditions, Gross said. As a result, park management now includes the concept of “connectivity,” which entails working with park neighbors and land conservancies to enable migratory corridors and pathways for species of all kinds to move.

“National park managers have small budgets to do things,” Rogers said. “You can treat pests. You can increase connectivity. You can try to get rid of invasive species. We can offer tools. But big-picture wise, the elephant in the room is the same. We need to cut our fossil fuel emissions and stop warming. There’s no getting around that.”

Photo by Patrick Jantz.

CITATION

- Rogers, B. M., Jantz, P., & Goetz, S. J. (2016). Vulnerability of eastern US tree species to climate change. Global Change Biology. doi:10.1111/gcb.13585

Originally published by Mongabay.